Brunelleschi’s Patent

The first recorded exclusive-right to an invention, construction of the Florence Cathedral's dome, and composer Ennio Morricone

Filippo Brunelleschi’s celebrity status pales in comparison to the Renaissance’s leading figures such as Leonardo DaVinci, Michelangelo, Lorenzo de’ Medici, and Galileo, but his achievements are tantamount to the most creative thinkers of any period.

The first patent ever issued by the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office was awarded to Samuel Hopkins on July 31, 1790 for a process for making potash fertilizer, launching a history of continuous innovation. Since the USPTO began assigning numbers in 1836, twelve million patents have been counted!

Two hundred and sixty-nine years before Hopkin’s achievement however, the first recorded patent for an industrial invention was granted to the architect and engineer Filippo Brunelleschi in Italy. By 1421, three decades before the birth of Leonardo da Vinci, Florence was the wellspring for the European Renaissance. Already, new methods of crafting tools and solving problems were proliferating in arts and sciences, and in commerce.

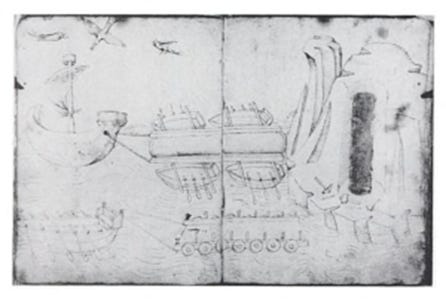

Brunelleschi’s patent gave him a three-year exclusive right on the manufacture of a barge with hoisting gear that carried marble—including massive slabs of Carrara marble from the famous quarries—along the Arno River. This drawing represents what the Florentine engineer referred to as “Il Badalone” (the monster).

Il Badalone from Taccola's De ingenis

Brunelleschi himself explained that his patent is the right to exclude others from using an invention, to protect the inventor’s intellectual work:

“Filippo Brunelleschi […] has invented some machine or kind of ship, […] and that he refuses to make such machine available to the public, in order that the fruit of his genius and skill may not be reaped by another without his will and consent.”

Brunelleschi introduces another crucial aspect of patent protection: a contract with society. In this agreement, the Republic of Florence grants the inventor the exclusive right to use their invention in exchange for publicly revealing the idea.

“[…] if he [Brunelleschi] enjoyed some prerogative concerning this, he would open up what he is hiding and would disclose it to all.”

In 1420, rumor was that Brunelleschi was keeping a new invention secret to prevent others from reaping the benefits without permission. A year later, the town's ruling council, the Signoria, granted him exclusive rights to his innovative device.

This led to a new decree requiring inventors to disclose their creations to the Republic in return for ten years of legal protection against infringement. As Venetian craftsmen and inventors migrated they sought similar protections, consequently spreading the concept of patent systems across Europe.

Brunelleschi was the individual who forged the pathway: By 1450, as the Medici bank expanded across every major European market, Venice began systematically granting patents.

‘Lofty Soul, Inspired Talent’

Naturally, any discussion about Brunelleschi inevitably centers on the great dome of the Florence Cathedral, his crowning achievement as architect and engineer. I first learned about the Cattedrale di Santa Maria del Fiore years ago in, of all things, a class on Medieval and Renaissance Engineering.

The ingenuity of Brunelleschi’s design and construction techniques quickly overcame the wide skepticism to convince the powerful Medici family to support his ballsy plan. As a powerful symbol of Renaissance Italy, the dome helped to extend the country’s influence far beyond its borders.

On our first trip to Italy in 2006, the train from Rome pulled into Florence without a glimpse of the city’s iconic cathedral. After the taxi maneuvered through a maze of narrow streets, the dome’s terracotta tiles and eight ribs in white marble appeared, proudly towering above the city’s modest skyline and embraced by the picturesque hills in the distance. A glorious sight!

Brunelleschi introduced a modern distinction between the roles of designer and builder, establishing architecture as both an artistic and scientific discipline.

Started in 1420 and completed in 1436 (with the lantern added in 1471), the dome represents a dramatic change in architecture and it marked the rediscovery of classical building techniques. With his friend the artist Donatello, Brunelleschi had studied and measured the ancient Roman ruins, which had been condemned and discarded along with its unpopular pagan beliefs and practices.

Brunelleschi's innovative design broke with tradition by constructing the dome without temporary wooden or iron frameworks to support the structure during construction. To do this he ingeniously figured out techniques such as the use of herringbone brickwork (see my photo below) and gigantic stone ribs to evenly distribute the dome’s colossal weight.

Rising over 54 meters above the ground, with a base spanning 35 meters and a total estimated weight of 37,000 tons, the dome was constructed using more than four million bricks.

Brunelleschi’s machines lifted massive weights to amazing heights. This drew the attention of leading engineers of the time, including Leonardo da Vinci, who documented them in his notebooks. Despite skepticism, the dome’s successful construction— without external supports—demonstrated the architect's mastery of engineering and project management.

In addition to Donatello, Brunelleschi was admired by many leading contemporaries who were inspired by his architectural and engineering genius.

Leon Battista Alberti published a book on painting (and dedicated it to Brunelleschi) that described the method of linear perspective that Brunelleschi had devised using geometry to create 3D drawings. This was a breakthrough in the arts of Western Europe, introducing a new way of thinking and seeing.

Leonardo da Vinci took notes on Brunelleschi's work in his sketchbooks, while future architects drew directly from the simplified, powerful style Brunelleschi pioneered.

Most impressively, Michelangelo relied on his studies of the dome of Santa Maria del Fiore while devising the dome for Saint Peter's Basilica in the Vatican.

Giogio Vasari, the renowned chronicler of the Italian Renaissance’s most creative individuals, reflects on Brunelleschi’s world-shifting impact in his book, Lives of the Artists:

“The world having for so long been without artists of the lofty soul or inspired talent, heaven ordained that it should receive from the hand of Filippo the greatest, the tallest, and the finest edifice of ancient and modern times, demonstrating that Tuscan genius, although moribund, was not yet dead.”

Octopus Brain

Spaghetti, Coyote Howls, and Whistles

Apparently, Italy is on my mind.

I recently watched a 2021 documentary on Ennio Morricone, the legendary film composer famously known for the awesome soundtracks for a series of Westerns that included A Fistful of Dollars; For a Few Dollars More; The Good, the Bad and the Ugly; and Once Upon a Time in the West.

These fiercely inventive collaborations with director Sergio Leone were breakthroughs, demonstrating that soundtracks don’t have to serve just as background for a movie. Both men recognized that music can play a starring role to raise a motion picture to a new level of experience for filmgoers.

Morricone, born in Rome in 1928, began composing music at the age of six and never ceased. By the mid-1960s, he became immersed in Italy's contemporary music scene and joined the experimental collective Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza, which was heavily influenced by John Cage's avant-garde techniques.

“As a joke I called these friends of mine,” Morricone said in a 2014 interview. “And I started telling them to do kind of a sound like groans or very strange sounds, and I started conducting them. And I also did sounds myself.”

In the documentary, we see how this period of risk-taking liberated Morricone to travel wherever his imagination took him.

Morricone was amazingly prolific, composing hundreds film scores, while receiving five Academy Award nominations before being conferred an Honorary Academy Award in 2007 for his “contributions to the art of film music”. In 2016, he finally won the Oscar for Best Original Score for Quentin Tarantino’s The Hateful Eight. He also composed some 100 works for the concert hall.

This video of The Danish National Symphony Orchestra in a live performance of The Good, the Bad and the Ugly is superb.

Numerous musicians have been inspired by Morricone, but this joyful performance by The Ukulele Orchestra of Great Britain is an all-time favorite.

Listening to Morricone’s music all week led to an experience of synchronicity.

On a walk to the post office, portions from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly kept looping in my head. Inside the grand old building, the pleasant earworm became more pronounced as I waited on line.

Once done, I stepped outside and immediately heard whistling and guitar notes that could not have been my internal soundtrack, even though it was surely a piece from another Morricone Western. Needing to locate the external source, I paced toward the vibrations as they got louder.

Halfway down the block I found two pedicabs modestly adorned in white flowers. A driver sat in one, the other with a boom box filling the street. The driver explained he was waiting for a newly married couple to emerge for a ride. Naturally, based on their choice of music it had to be a shotgun wedding.