Bad Medicine

Private equity’s strategy of corporate bloodletting harms patients, doctors, and the healthcare system at large

It’s a golden oldie: ‘Do no harm.’ Attributed to the original Hippocratic Oath, this central principle for medical practitioners is the earliest expression of medical ethics in the Western world. The dictum remains important for physicians today even as it has evolved over the centuries.

Whether private equity firms have their own maxim for ethics like physicians is doubtful. But if they did it would likely be this: ‘Insulate yourself from the consequences of your actions’.

Private equity investments extend across a variety of healthcare entities, including hospitals, nursing homes, and physician practices—and the outcomes are amazingly rewarding for PE teams.

Analysis by Bain & Company shows that from 2010 through 2021, the median internal rate of return (a key metric used to measure the performance of a fund and the potential profitability of an investment) for healthcare private equity deals outperformed those in all other industries by about 6 percentage points—27.5% vs. 21.1%

Stephen A. Schwarzman heads Blackstone Group, the world’s largest alternative asset manager with more than $1 trillion in assets under management. In his book on the pursuit of excellence he describes the magic of private equity investing:

“A classic LBO works this way: An investor decides to buy a company by putting up equity, similar to the down payment on a house, and borrowing the rest, the leverage. Once acquired, the company, if public, is delisted, and its shares are taken private, the ‘private’ in the term ‘private equity.’

The company pays the interest on its debt from its own cash flow while the investor improves various areas of a business’s operations in an attempt to grow the company. The investor collects a management fee and eventually a share of the profits earned whenever the investment is monetized.

This game plan works so well for the private equity folks that investment bankers look like poor cousins in comparison. In fact, Schwarzman’s income in 2022 was 50 times that of the CEO of Goldman Sachs!

Blackstone isn’t an isolated case. Firms like Apollo Global Management, KKR, and Carlyle Group follow a similar strategy—buying companies with minimal capital of their own, burdening them with substantial debt, and aggressively slashing costs.

For healthcare companies, private equity’s involvement often leads to declines in service, usually from understaffed facilities.

Private equity’s soaring involvement in U.S. healthcare is stunning, with over $1 trillion invested in the last decade. According to a report on this trend:

“Private equity firms prioritize short-term profits, typically moving on from their health care investments within three to seven years. While PE investment in health care may improve operational or technological efficiencies, there are concerns about the effects on cost, quality, and utilization of care.”

A recent study from Harvard Medical School published in JAMA shows private equity ownership of hospitals increases medical risks. Patients in hospitals acquired by PE firms were more likely to suffer falls, infections, and other maladies resulting from lapses in hospital safety and quality.

The study looked at data from over 600,000 hospitalizations at 51 private equity-owned hospitals and compared them to more than 4 million hospitalizations at 259 non-private equity hospitals between 2009 and 2019. Sadly, we see worse outcomes in hospitals owned by private equity—particularly in preventable complications.

It’s disturbing how frequently a lack of deep industry knowledge is cited in reports of Wall Street deals gone bad.

While PE firms inject much-needed capital and management expertise into struggling hospitals, the potential downsides exist within the model. Debt-loading in most private equity buyouts can potentially shift priorities from patient care to monetary returns.

Under Carlyle Group’s ownership, HCR ManorCare, the second-largest nursing-home chain in America, filed for bankruptcy after years of financial decline. A Washington Post investigation found that health-code violations at its facilities surged by 26% from 2013 to 2017.

Carlyle’s 2011 deal extracted $1.3 billion from ManorCare and left it saddled with unsustainable debt. The company sold off most of its real estate and faced rent obligations that strained finances, leading to layoffs and cost-cutting efforts that compromised patient care.

The Post article highlights an understated problem that often turns up in unsuccessful deals on Wall Street:

“Carlyle was a very interesting group to deal with,” said Andrew Porch, a consultant on quality statistics to whom ManorCare referred questions about health-code violations. “They’re all bankers and investment people. We had some very tough conversations where they did not know a thing about this business at all.”

Relying too much on the doctrine of financial engineering (slashing costs, extracting value, and leveraging assets) over operational expertise, decisions can undermine long-term growth or efficiency. While financial metrics may initially get a boost, lasting success often falters—ultimately hurting employees, patients, and the overall business.

Who calls the shots when lives are on the line?

In a 2023 interview, Gretchen Morgenson attests to how healthcare companies are especially susceptible to private equity’s cost-cutting measures.

PE firms are increasingly taking control of emergency departments, with groups KKR and Blackstone overseeing 40% of such services across the U.S., according to Morgenson. Billed as a strategy to boost efficiency and patient care, doctors warn it’s having the opposite effect: profit-chasing is eroding service quality.

The impact is starkest in rural areas, where healthcare choices are already scarce. Many patients, unaware their emergency care is now run by private equity, face a troubling reality: corporate profit often takes precedence over their wellbeing.

It’s very simple for Morgenson:

“You're talking about the coffee and donut that private equity owns. Okay, if you don't like the coffee and the donut, you'll go somewhere else. But if you're in need of an emergency department and this is the only one in your town and you have to go there and it's run by a private equity firm that is putting profits ahead of patients, that's a problem.”

Unsurprisingly, private equity's grip on U.S. healthcare is facing resistance from physicians, with groups like Take Medicine Back rallying against corporate control. This is a response to the acquisition of 5,300 physician practices between 2022 and 2023, the culmination of a decade in which PE funneled nearly $1 trillion into healthcare.

The Wall Street Journal reports many doctors hold strikingly negative views of buyout firms (61% negative vs. 11% positive) and increasingly are taking political action against them. Now that these medical professionals are employees of hospitals or corporate groups, they feel they’ve lost autonomy to make clinical decisions.

So, can profit be balanced with patient care in an increasingly corporatized system? Vicki Norton, president elect of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine, doesn’t believe it can:

“It’s one thing when private equity invests in a burger joint or a clothing line. But this is healthcare, it’s a life-and-death issue, and private equity just has no place in it.”

Bloodletting, a practice performed by surgeons from antiquity until the late 19th century, is not entirely defunct. Too often the giants of private equity abuse their power, behaving like leeches rather than constructive owners of healthcare companies and principled supporters of employees and patients. And there’s absolutely nothing ‘humorous’ about that.

Octopus Brain

Left to Their Own Devices

Israel’s recent attack against Hezbollah targeting pagers and cellphones is causing Iranian-backed militant groups across the Middle East to rethink how to protect their communications gadgets.

“Extreme precautions will be taken, and we will keep devices away from us,” said a senior commander in the Jenin Battalion, a coalition of West Bank fighters led by Palestinian Islamic Jihad. In fact, his operatives have already avoided cellphones and recently ditched handheld radios they suspected Israel of hacking.

Despite the logistical obstacles though, all is not lost. It’s just possible a workaround for the hostile fanatics is an arm’s length away.

A friend proposed in jest that Hezbollah might consider rigging selfie sticks to each fighter. He conjectured that positioning a Bluetooth-equipped electronic device a couple of feet away from their body would surely limit the impact of any explosions.

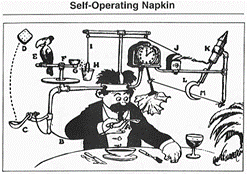

Such a ridiculous invention—let’s call it an ‘Explosion Impact Reducer’—immediately reminded me of Chindogu, the art of the unuseless idea, a kindred sprit to the whacky creations of Rube Goldberg.

In Japan Kenji Kawakami is the grandmaster of Chindogu. He built a curious philosophy around his logic-defying gizmos and gadgets that work in theory but are utterly impractical in real life. Pure in vision, Kawakami’s anarchic inventions serve no commercial purpose and are barred from being patented or sold.

In his major work, The Big Bento Box of Unuseless Japanese Inventions, Kawakami writes:

“The successful Chindoguist approaches his subject in much the same way that a serious inventor would: searching for an aspect of life that could somehow be rendered more convenient and concocting a method for making it so… Chindogu are inventions that seem like they’re going to make life a lot easier, but don’t. Unlike joke presents built specifically to shock or amuse, Chindogu are products that we believe we want—if not need—the minute we see them.”

The Big Bento Box of Unuseless Japanese Inventions—filled with 200 Chindogu, including Walk ‘n’ Wash Ankle-Attachable Laundry Tanks and Duster Slippers for Cats— is fun stuff and ideal for a coffee table. And if you don’t own one of those, I recommend the Chindogu coffee table built by Kramer in this Seinfeld episode.

Disclaimer: Content provided in this newsletter is intended to be used for informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice or any other kind of advice.